|

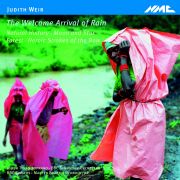

from the booklet notes to Judith Weir: The Welcome Arrival of Rain (BBC Symphony Orchestra & Chorus cond. Martyn Brabbins; NMC D137, released January 2008):

Wisdom is not a quality for which one often looks to contemporary music. In an age suspicious of confidence, when so many of our familiar sources of enlightenment have been cast in doubt, we look to art mostly to give us comfort or to reflect our uncertainty. Wisdom, we tend to imagine, is elsewhere – the privilege of calmer minds and surer times.

Calmness and sureness are among the qualities that distinguish Judith Weir both as a person and as a musician, and the ironically raised eyebrow with which she conveys them may even be the precondition under which wisdom is available at all to us today. In encountering Weir’s music we often seem to find her engaged on a search for wisdom, and the places she has learned to look for it account for some of her work’s most characteristic locations. This is often a matter of drawing in folk sources or alternative traditions of thought: evoking other places, other times, and other ways of seeing. The texts of the song cycle Natural History tell of a world in which a passing observer can casually be named as Confucius. But the man Confucius sees swimming in the waves could be a figure from our own world – ‘He took him for someone in trouble / Who wanted, who wanted, who wanted to die’ – and we realise that what Weir has sought in these ancient texts is not an aesthetic object to hold at a distance but a mirror for her own, modern quest.

Her preoccupation with nature, likewise, derives less from an impulse to escape our man-made world than from a concern not to ignore the lessons nature has to teach us (and a sense of foreboding about what might happen if we do). A recurring irony in Weir’s songs and operas is of animals who seem to know more than their human observers. Presenting human characters who must learn to listen to the wisdom of nature is one way Weir has of turning our conscious desire or unconscious need for enlightenment into a story. Folk tales are another source of stories and images, and their dark forests and talking birds are, one feels, something Weir takes up with a wry amusement at the notion that they might make us wise as well as an enchantment that the possibility has even been raised. She knows they are stories, but also knows that stories are what we have.

By such means wisdom is made available for our own time, and Weir is able to find her place in a tradition closer to home. Each piece here draws something of its character from its destined performers – one German, two English and, most recently, two American orchestras – and yet, different as they are, as a group they attest powerfully to the concerns that unite Weir’s output. Most unexpected, perhaps, is the composer’s suggestion that the first four pieces on this disc make up a ‘nature symphony’ like Mahler’s Third, with movements for chorus and for vocal soloist alongside purely orchestral ones: a varied suite of tone-poems at the head of which one might imagine the Mahlerian motto ‘What nature tells me’.

© 2007 John Fallas

continued here (note on The Welcome Arrival of Rain)

for more information, to reproduce any material from this website, or to commission new articles or programme notes, please contact jfallas @ worldisnow . co . uk (no spaces) |

|

![]() |